|

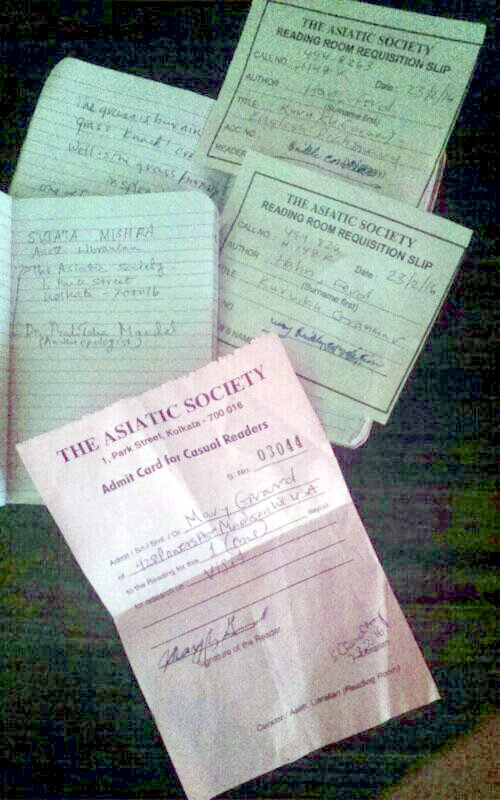

The Orient has always been a facination to the west. Ancient trading routes soon became pathways for Imperial expansion, that exposed places and people to each other, the "mysterious other." Exposure to the East led to an exploration into how the "other" thinks, behaves, believes. Orientalism, Indology, and Asiatic Studies became the forbearers of archeology, anthropology, and linguistics: the study of ancient places, people and language. Likewise, scientific study of plants, animals, and lands spawned a wide range of theories such as early genetic determinism and evolution. The Asiatic Society in Calcutta, and eventually in Bombay and then Delhi was established by the English to capture the studies conducted in India particularly, but throughout Asia. Collections hold ancient documents in Tibetan and Chinese as well as Sanskrit and Persian. Not everything went to England after the British left India. And the fascination with everything Indian was shared not only by the West, but by Indians from all backgrounds. Contributions to the Journal, Archives, and Library have been collected over the centuries from a variety of sources. Today we went to see the Asiatic Society in Kolkata. I went to seek what I could learn of my great great grandfather, Ferdinand Hahn, knowing he had published some articles. Indeed I found the books he had written of the Kurukh language. Three books, first editions, each in delicate condition after 100 years in the moldy and dusty archives. I want to share the process I had to go through to find these three books, and also three articles, all published between 1900 and 1904. , but not to poke fun at the Indian way of doing things, nor to romanticize it. Just to simply state what one must patiently endure to accomplish a simple task. At the very least my librarian friends may appreciate this story. Upon entering the building, which is the "new" building that was built concealing from the street the original building, we were asked to sign in. I went with my cousin and sister-in-law. I asked about the archives so they sent us to floor 2 where there was a Museum. We took the elevator (the kind with double cage doors that must be mannually open and shut). Various people standing around directed us to a desk. I explained to the woman behind the desk what I wanted in the archives and if the other two could look at the museum. "Have you shown your passport?" she asked? I was puzzled, for no one had asked to see ID. "No," she continued apparently annoyed at our niavete, "You must sign in at 3rd floor and then go to Library on 1st floor to get your pass." While this confused me about which floor to go, I dutifully followed the instructions and indeed found an office on the 3rd floor that asked for us to record our names with passports. Then down to 1st floor (in US that would be 2nd floor), where we were met at the elevator by a man who would take our bags. Again registering our names in another records book. We filled out a form each that was in triplicate and the supervisor signed each and gave us the pink copy. This granted us permission to go to any part of the building. By the end of my two hour visit I would sign 7 different registers. We returned to the Museum floor and the original woman was very pleased to take the information I had shown her before. As she went to search the archives, we went through the library that housed some incredibly old documents written in various languages on a variety of papers, wood, stone, copper, etc. She returned at the end of our walk around the musty humid room to state there was nothing in archives, but something would be available in the library. I went down one floor again to look through the card catalogues and then filled out the forms and gave it to the circulation desk where someone dissappeared in search of the books. I then approached another woman who appeared to be the main librarian. I inquired about the journal articles and asked her what had been the process for submitting an article. She was not forthright with information until I explained this author was my great great grandfather. Then suddenly her face was transformed by joy and she responded with maternal care. At the turn of the last century a Dr. Greirson (may have written name incorrectly) conducted a language survey of India. When he came to the Jharkhand region he met Ferdinand Hahn who was studying the language of the people's that he lived and worked among, the Oraon and Asur tribal people. He suggested that Hahn write his findings to the Asiatic Society. The librarian said that submissions get paid something today, but she wasn't sure if there was anything paid in those early years. My guess is that would have been one reason why Hahn submitted the articles, some supplemental income for their meager income. I wasn't prepared to do any deeper research this time, but I thought I'd look up some other German missionaries who had worked on other languages, notably Alfred Nottrott there was nothing. This suggests to me that Nottrott, who wrote about the Mundari language and people, was submitting papers only to German Orientalist journals, not British. I understand that Nottrott was from a better situated family and had higher education then his peer, Ferdinand Hahn, who came from a shoemaker family and was not as well supported financially. The Nottrott family had close associations with scholars in Halle and Berlin in German. Nottrott's work in Mundari eventually earned him a Doctorate degree in Germany. Not that Ferdinand Hahn was overlooked for his contibution to tribal studies, his scholarship, along with his community work in health and education earned him the Kaiser-E-Hind award in British India. The librarian called over another woman who was the Anthropologist of the Asiatic Society. I was surprised to understand most of what they were discussing in Bengali. I asked, in English, if I had heard correctly that she knows of Ferdinand Hahn. "Oh yes, I'm knowing. No, I have not read his books, but I am knowing the name." I was asked what field of study I was in. After a feable attempt to explain they told me what the right answer is. I am coming from the literary field. As we talked I confessed that my original idea was, and still remains, to write a novel based on my great great grandmother. However all I have found so far is about Ferdinand Hahn, For this reason I recognise the need to write a biography of him first, then write about her in historical fiction. For it still remains shrouded in mystery about the life of women in that era. My motherly librarians both shook their heads in contented agreement and requested I send them a copy.

I end with a lone song of the Asur people's that Ferdinand recorded in one of the articles I saw today Bir do ranjolena Bir geter geter Tanka bir ranjilena Barea buggire The grass is burning Grass knack! crack! Well is the grass burning In splendid beauty I don't know the significance of burning grass to the culture of the small, now extinct, tribe of Asurs. They were iron workers. Ancient people working in iron. Fire was the life blood of their craft. The embers of my craft as a writer are being fanned by this trip to India, through encounters like this one today. Oh can you see the splendid beauty?

1 Comment

|

Mary GirardI will be traveling and visiting India, with my Father. Our primary destination in India is Ranchi, Jharkhand. We will also visit other towns and cities in that north-eastern region as well as other places in India. Archives

May 2016

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed